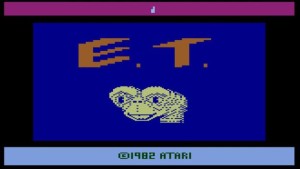

The ET Game – learning how to fail better

The history of the videogames industry is littered with the corpses of terrible games. Many of the gravestones are for games based on feature films and today’s story in the BBC Magazine about the epic failure of the ET game – described as the worst video game in history – is a majestic tomb to misadventure.

The history of the videogames industry is littered with the corpses of terrible games. Many of the gravestones are for games based on feature films and today’s story in the BBC Magazine about the epic failure of the ET game – described as the worst video game in history – is a majestic tomb to misadventure.

Making a game of an existing story is always a risky venture. Translating an idea from one format to another is notoriously difficult. Once realised on a movie screen or imagined off the pages of a book, the plotlines and indeed the character behaviours are fixed in the minds of the audience. Retelling a great story often makes it more vivid but replaying the same story will only ever have limited appeal because we know that, whatever we do, the outcome will always be the same. Any attempt to recreate a well-known tale with any intrigue is going to be a struggle – we know how it’s going to end – there’s no surprise in the game play just frustration.

Games set in story “worlds” have fared much better. Extending the Star Wars universe or even Lego-themed variations of Indiana Jones or Batman give players the chance to make the stories bigger than the originals. Placing the action in a familiar environment and letting players go beyond The End is a perfect way to cater for a demand for more – there is no take-your-breath-away revelation about discovering who Luke Skywalker’s father is in a game of the film but sitting in an X-wing fighter and liberating new worlds from the Empire will always be thrilling.

While the ET game is a good example of the dangers of relying too much on a ‘brand name’ over gameplay it’s real lesson is more profound.

Although the game effectively wiped out Atari, it didn’t kill the industry. The resilience of the gaming community reflects a key feature of the games it makes and plays. What successful games do brilliantly is teach us how cope with failure. Indeed, while non-gamers might imagine games to be defined by “fun”, most gamers would say they are characterised by grinding effort and repeatedly getting it wrong. What good games do is show us how to try again: they highlight our mistakes, demonstrate the value of perseverance and encourage and reward success.

The story of the ET game shows this principle in practice. The designer, Howard Scott Warshaw, didn’t just create the worst video game ever he also designed one of the best – Yars Revenge. Twenty years after the ET game was buried, the global games business is the world’s most successful entertainment format, surpassing television, film and publishing combined. If there’s one thing games development teaches us, it’s how to fail – and learning from our failures is how we get better.