Exploring Interactive Narrative – Traditional storytelling

In an increasingly multiplatform, multiformat world, the way we combine activity with storytelling fascinates me. Although usually associated with video games, I think the principle of ‘interactive narrative’ applies to all the domains where we punctuate presentation with participation.

[To clarify, I’m using the following definitions: ‘story’ describes characters, events and plot; ‘narrative’ describes how the story is told, or more pertinently how the experience is structured.]

The use of story lines within video games is an established mechanism to improve engagement and provide structure for play. In his excellent blog, Chris Bateman identifies six categories of game narrative which, almost inadvertently, describe the main ways we interact with any content. I have adapted and developed Chris’s ideas slightly:

- Linear narrative

- Parallel narrative

- Non-linear narrative

- Branching narrative

- Dynamic narrative

- Simultaneous narrative

Over the course of this series, I’ll try to unpack some of those concepts and identify where real opportunities lie.

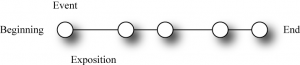

Traditional Linear narratives reflect the historical, single path and singe conclusion storyline of novels, theatre and film. Even though there may be periods of user activity, the audience is a passive receiver of information crafted by another’s hand. It is the most common and understood form of narrative where all users travel the same path and come to the same ending.

The linear narrative predominates in single-player video games, exemplified in titles such as Halo and Metal Gear Solid. Within this model, users must successfully complete a stage before receiving the next episode of drama. These stages of player activity exist within envelopes of freedom that offer the illusion of control between set pieces. The dramatic elements of these cut scenes provide both a reward for progress and a motivation for continued participation. These games emphasise the pivotal role of the player in the story by establishing a role-playing scenario – the user plays the central character. Yet the loss of player control, however temporary, during these cut scenes undermines notion that the user determines the games outcome; as a consequence they are not universally appreciated.

Just watching video sequences, even if you pace them yourself, is not fun. It’s not even really a videogame. It’s just stupid remote control tricks. (J C Herz, Joystick Nation, 1997, p147)

Herz identifies the challenge of managing expectations, at one moment the game is reliant on user participation, the next events are out of his control. Indeed if game play is “a series of interesting choices” as Andrew Rollings and Dave Morris say (Game Architecture and Design, 2000, p39) then without this interactivity, the resource ceases to be a game at all. However, even in games that offer a single plot line delivered through cut-scenes, there is opportunity for ‘interesting choices’ and each user’s experience is still slightly different because of the differing pace and depth of exploration. Some users will explore every corner and avenue of each stage, determined to discover every element of the environment. This slow and methodical procedure is in marked contrast to players who race through stages, intent on completing each one as quickly and as efficiently as possible. By choosing the critical path through the resource and charging across the game world at breakneck speed, these lightning players inevitably will miss elements and subtleties of the storyline and context although this may not necessarily affect their personal enjoyment.

This ‘striped’ approach to content is extremely common, not just in games. The approach relies on the illusion of control to maintain ongoing participation – there is relatively little space or opportunity for variation (even during the periods of user activity). It’s the commercial television model for scheduling – break the programme with advertising (when the viewers can do their own thing – so long as it only takes three minutes).

The challenge for producers is making the experience as responsive as possible and that means using the periods of activity to personalise the passive elements before moving on to the next episode.

The whole Interactive Narrative series is:

7 Responses to “Exploring Interactive Narrative – Traditional storytelling”