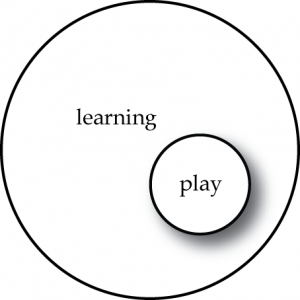

Where play meets learning

Play’ and ‘games’ are dirty words to many traditional educationalists because of their connotations of trivial, wasteful and indulgent activity. It might hark back to our WASP-ish philosophy that only hardship and suffering are good for the soul. Even the seminal play theorist, Johan Huizinga, argued that play is “an activity connected with no material interest.” (1) Huizinga defined play as:

- free

- meaningful

- carried out for its own sake

- spatially and temporally segregated from the requirements of practical life

- bound by a self-contained system of rules that holds absolutely

However, play is a valuable means of facilitating learning because the act of playing encourages imagination, creativity and spontaneity. These are are key elements of cognitive plasticity – the ability of our brains to flex and adapt. Many evolutionary biologists and psychologists suggest that play is a unconscious, instinctive and practical pursuit that is purely a training ground for adulthood but Brian Sutton-Smith (2) believes that the dynamics of play mirror the biological processes that lead to adaptive variability, that is, play is characterised by quirkiness, unpredictability and redundancy.

Play is an intrinsic part of learning where learning is the development of thinking (cognitive), emotional (affective) or physical (psychomotor) skills. Indeed, Piaget (3) and Vygotsky (4) both contend that play, in its various forms, is central to development from birth to adulthood. The instinctive play of children is good at developing the range of psychomotor and affective skills but not so effective at cognitive ones. For example, simple games of ‘shops’ help children understand the social interactions involved in basic shopping and even the physical movements required to use a cash register but fail to instil any sense of value for money. Piaget defined play as a process of assimilation of experiences through which a child reaches higher levels of cognitive development.

However, for play-developed learning to be meaningful outside its own context, it must breach the magic circle (what Huizinga means by play being “spatially and temporally segregated from the requirements of practical life”). In other words, the learner must be able to transfer the skills developed within the game to other, real world contexts if the playing can affect wider experiences. This transfer is what makes play-based learning extrinsically valuable to the player.

———-

(1) – Huizinga, J., (1950), Homo Ludens, Roy Publishers, New York (n.b Hector Rodriguez has an excellent summary of Huizinga’s work)

(2) – Sutton-Smith, B., (1997), The Ambiguity of Play, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

(3) – Piaget, J., (1962), Play, dreams and imitation in childhood, W. W. Norton & Company, New York

(4) – Vygotsky, L. S., (1962), Thought and Language, Wiley, New York

Trackbacks/Pingbacks

[…] This post was mentioned on Twitter by Paulo Simões, Carlton Reeve, Carlton Reeve, Carlton Reeve, Gerry McAteer and others. Gerry McAteer said: RT @UpsideLearning: Where play meets learning http://tinyurl.com/3x4he7u […]

[…] Play and learning are intrinsically linked. Indeed, we learn in three ways: repetition, play and dialogue. From the moment we are born, play is a basic human desire. […]