Challenge

I’ve written a couple of posts already about motivation (the motivation to learn and motivational momentum) but today I want to explore some of the issues associated with that powerful driver: challenge.

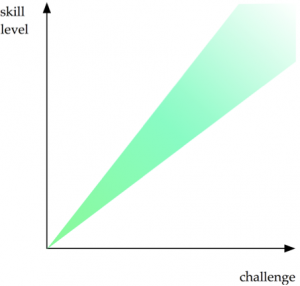

The ability to overcome some conflict is central to the engagement of most narrative experiences. Similarly the level of challenge associated with any game, or stage within a game, is critical in maintaining and encouraging participation in it. The challenge or difficulty presented by any voluntary task needs careful management if it is to keep the user taxed appropriately, that is suitably stretched but not frustrated. Csikszentmihalyi’s theory of Flow describes a ‘channel’ where participants enjoy the optimal experience of play-suspended consciousness while developing their skill.

If the challenge is too much for the user’s skill level, the experience quickly induces anxiety and overwhelming frustration; if the skill level outstrips the challenge, the user is swiftly bored and disengaged.

The key to successful engagement depends on setting the appropriate level of difficulty for the user’s current skills. The difficulty of any game is the product of various elements:

- The quantity of the tasks

- The complexity of the task and

- The pace at which the tasks are presented

The appropriate level of challenge is dependent on the differing needs and levels of expertise of the target user group and even on the type of task. Games employ different strategies for determining a satisfying level of difficulty. At the simplest level, the game offers options at the start of play such as easy, normal or hard. These levels might manifest themselves in the sheer quantity of conflicts to address as in Sim City with its ability to turn on more features or the ‘intelligence’ of the opposition as in electronic Chess and its ability to ‘think ahead.’ Some games, such as Silent Hill 2 recognise that different types of task might require alternate settings. In this case, the game offers players settings for the puzzle and action aspects of the experience. Ritual offers users control over both the level of challenge (between ‘casual’ and ‘extreme’) and the assistance given to players by other characters (ranging from ‘quickly’ to ‘never’). The Grand Theft Auto series operates a ‘mixed economy’ of challenge with the free-roaming environmental playground offering user-defined activity and specific missions giving greater reward for higher levels of difficulty.

Rather than giving the user control of difficulty, some games, exemplified by the car-racing genre, provide adaptive handicapping of the computer competition. In this approach, the system alters the intelligence of the non-player characters according the player’s current performance to provide opposition that is slightly above and below the user’s current competence.

The most sophisticated forms of difficulty setting offer dynamic and escalating levels of challenge. Elaboration Theory is a learning model that advocates a progression of successively more complex problems. Proponents argue that the clear sense of progression is a powerful motivator. However, these challenges need careful sequencing if they are to keep offering players the optimal experience. Most story-based games like Metal Gear Solid provide increasing levels of challenge where players ‘graduate’ to more difficult levels by achieving the desired goals. Each successive level assumes a degree of competence as demonstrated by the successful completion of the previous one. However if the leap is too great, the challenge is too much for the potential skills development; too small and the player loses his sense of progression.

Players take risks in games because the consequences are rarely significant in the real world but it would be incorrect to believe that there is no comeback from repeated failure. The cost of lack of progress in a game can range from simply lost time to loss of hard-earned privileges and reputation. Particularly in multiplayer games, long terms failure has a genuine social impact, as one veteran player of World of Warcraft commented: “No one wants to be a member of a guild that always wipes out.”

It is far to say, therefore, that the measure of the effectiveness of a game is its ability to develop player skills to tackle ever more challenging scenarios. As players learn, so clever games increase the level of difficulty to maintain the user’s position in the flow channel; getting the level wrong leaves players bored or frustrated. Isn’t that the main cause of disruption in learning?

How many educators need to play a few more games?