Educational games

Yesterday I spoke at BAF Games. This is a summary of my ‘Play with Learning’ talk. I have embedded links to supporting information into the post . Sadly, I couldn’t capture the lively Q&A session afterwards.

I made my first game as a young teenager – a board game so incomprehensibly complex and tedious, it only ever had one player. Me. I programmed my first computer game at the age of 14, using the machine code printed in the back of a Sinclair User magazine. It took a week to input, twenty minutes to load and thirty seconds before it crashed. Despite those experiences, I spent innumerable hours playing games on my ZX Spectrum.

At the same time, although not entirely related to my game-playing, my school-based education collapsed. I left school with a clutch of poor GSCE’s, a single in A level Government and Politics and a report that read straight ‘E’s.

For me there’s always been a link between games and learning, but it’s taken years of industry and professional experience including my time as a BBC Commissioner and a PhD in the educational psychology of games to fully appreciate the potential benefits.

I am a game player but I’m also a lifelong learner. I am a passionate believer in the potential of education to change lives. I believe that learning is something that can make the world a better place. It can transform society, culture and the economy by catapulting people out of often horrendous situations and helping them realise their potential.

Learning is not an onerous activity – we love to learn. Everyone loves to learn. The thrill and satisfaction of acquiring some knowledge or skill, or overcoming some challenge by developing a solution is universal. Just because the experience of school poisons some attitudes towards education it doesn’t mean that learning ever loses it’s ability to delight.

Play and learning are intrinsically linked. Indeed, we learn in three ways: repetition, play and dialogue. From the moment we are born, play is a basic human desire.

Who could deny that play is enormously attractive? Regardless of whether it is computer-based or real-world, sports and games are a universal passion. You only have to consider the viewing figures for the Olympic Games and the World Cup to recognise that play is universally appealing. The last World Cup had more than 3 billion viewers making it the single biggest collective event in human history.

But it’s not just passive entertainment. In terms of activity duration it wouldn’t be unreasonable to say that video gameplay is unprecedented in human history: some estimates suggest that we play three billion hours per week, 150 million people play FarmVille each month. That’s an astonishing amount of time and reach.

Some of the most fervent game players are exactly the same people who disengage or drop out of school and play no further constructive role in society. With their devotion to gameplay, it is easy to see the attraction of making education more game-like.

In education the appeal of games represents a form of Holy Grail. The idea that a disaffected disinterested disempowered teenage boy (or girl) might spend hours and hours of their own time tackling a formidable problem, want to talk about it with his friends, and pursue it until he succeeds is something that any school teacher would love to be able to mimic. A gamer will willingly invest more than the 100 hours needed to complete a game like GTA 4; that’s the equivalent to half a GCSE or 10 credits towards a Masters degree. Gaming seems like the obvious solution to reengage young people.

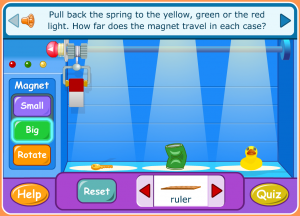

Sadly, we tend to deliver them ‘games’ like this:

We deceive ourselves that these activities are going to make the same impact as the games we play at home. In fact, if we’re honest, this sort of “educational game” is neither educational or a game because it doesn’t possess the characteristics of either.

Perhaps it is unreasonable to compare educational resources like this with commercial off-the-shelf games. After all Grand Theft Auto 4 had a $100m budget; that works out at $1m per hour of activity. Most educational resources have a minuscule fraction of that. But sadly, even the easy-to-implement feedback and rewards systems don’t come close to what the entertainment-focused competitors provide.

The other problem with educational games is we’re not all gamers so for some the prospect of playing a computer game isn’t that appealing.That said, I’m not suggesting that we can’t all appreciate games and gain something from them.

Many of the perceived benefits of educational games are a consequence of the Hawthorne effect where the extra effort committed to introducing and testing the game are the reason for improved performance, not the game itself. Actually, there is very little evidence to suggest that playing games, without any further contextualisation, delivers any transferable learning at all which is why I’ve said, provocatively, games teach us nothing.

Perhaps when you take these resources apart, closer inspection reveals very few gaming characteristics. In my post what is a game? I identify the following core characteristics that turns an activity into a game:

- Agency

- Engagement

- Suspension of disbelief

- Competition

- Rules

- Goals

- Progression

- Empathy

- Rewards

I haven’t included fun in that list. For me, fun is a bonus in gameplay but it is by no means a defining characteristic. Indeed most games that I play are not fun. Most games that I play, if they are worth playing, are characterised by long, grinding effort. I rarely finish games feeling euphoric – more often I feel exhausted but satisfied. What makes the effort worthwhile is the quality of the rewards.

Many of those game characteristics are intrinsically associated with learning. Games meet learning in the following aspects:

- Opportunities for reflection and evaluation

- Access to feedback on performance

- Record progress

- Purposeful interactivity

- Achieving learning objectives

- Opportunities to collaborate, investigate or experience

- Chance to correct and learn from errors

Actually, I think games teach us lot.

So, in spite of my criticisms of “educational games,” I still believe passionately in their potential to inspire learning. And I think their real educational value lies in four areas:

- Cosmetics – making the unpleasant more palatable

- Confidence – offering the chance to practise and fail softly

- Catalyst – as a spring board to further investigation

- Collaboration – as a means of pooling our intellectual and social capital

I think that learning is of the utmost importance to our society and our world .While I don’t believe that games are a panacea, I do believe that they offer a unique way to reach and develop our potential and tackle many of the problems we face.

Playing games often brings out the best in us. It inspires ingenious solutions, hard work and perseverance and global collaboration. In games we believe that anything is possible and that we are capable of anything. Surely those are traits that we should bring to bear on life.