Learning stories

If we believe that learning can be a profound, life-changing experience, we cannot merely scratch the surface of a subject but must burrow deeply to its core. No question worth answering is easy. It takes time and effort.

If we believe that learning can be a profound, life-changing experience, we cannot merely scratch the surface of a subject but must burrow deeply to its core. No question worth answering is easy. It takes time and effort.

Increasingly many learning providers seem scared of expecting this level of commitment. Many people mistakenly believe that our attention span is waning, especially when it comes to ‘serious’ business. I’d like to suggest (from the evidence of captivating entertainment like Harry Potter and Lord of the Rings) that well told stories retain their ability to hold our gaze and concentration. It is not learning that turns us off; it is the tired, lazy and dull materials and delivery that makes us glaze over and give up.

Stories captivate.

Good stories make a promise: if you persevere, you will be rewarded. Learning makes this same promise.

No-one ever tires of the delight generated by new learning. Perhaps counter-intuitively, true learning does not confirm prejudices, rather it challenges assumptions and helps to alter one’s perspective in order to accommodate new understanding. However, this change in behaviour is rarely, if ever, accomplished through intellectual argument alone. Indeed, one of the tenets of Constructivism is that

direct instruction is unlikely to change belief systems.

Change is a head and heart activity: it requires conscious vulnerability. In order to encourage openness we have to engender a degree of trust: we make a covenant with the learner that says by weakening their assumptions, they will become stronger. Only attachment can build trust.

Learning has to create space and opportunity for emotional engagement.

When we hear a well told story, our brains respond as if we were experiencing the situation first-hand – it’s a process called neural coupling. It means we feel what the characters feel. We can significantly enhance learning experiences by integrating the story elements such as drama, character and feeling.

Stories create shared worlds, they are inherently social, they offer counsel, comfort and connection to the lives of others: they help us make sense of life. Stories can be approached from a variety of intellectual and developmental levels because everyone has the opportunity to find a measure of delight, to stretch their minds and to enquire and explore the possibilities.

Stories work so well for learning because they have a set of conventions. They provide a stable pattern which allows for specific types of information and logical relationships. “Stories are about characters whose actions are sequentially organised and causally related. Characters have roles and the roles are motivated.” say Temple & Gillet in Language Arts: Learning processes and teaching practices.

One of the features that make stories effective dramatically is that they naturally embrace difficulty and progression. Stories are characterised by increasing tension where characters overcome challenges and conflict only for new ones to arise. It all leads to the climax and a satisfying conclusion (if well told). Learning uses the same mechanism. We know how powerful this can be if we simply recall those brilliantly engaging teachers from our childhood.

In their book, Integrating Learning through Story, Carol Lauritzen and Michael Jaeger suggest we can utilise the power of stories for learning in a number of ways. I think the three most powerful (and relevant for online) are:

- story as catalyst

- story as framework

- story as resource

The first way of using stories for learning is as a catalyst: use a story to gain attention, excite, intrigue and challenge then follow up with some activity and reflection. Short, single ‘chapter’ stories such as parables work best for this type of approach. You don’t want too many distractions (or subplots) in the tale so that you can focus on a particular point afterwards.

When stories have multiple elements, numerous chapters or subplots, you can use them as a framework. At each natural break in the tale, you can introduce some activity or reflection. This only really works during a ‘beat’ in the story, that is when a natural breathing space occurs. An excellent example of this is the children’s story, The Very Hungry Caterpillar by Robert Carle. Carle makes the turn of every page an opportunity to ask the listening child a simple question such as “How do you think he feels now?” or “Why do you think he’s made that cocoon?” These are questions that don’t disrupt the flow but increase engagement by involving the learner in the storyline. Used appropriately, the reflection points build, not dilute, the dramatic tension and they do nothing to undermine the story’s climax.

When stories have multiple elements, numerous chapters or subplots, you can use them as a framework. At each natural break in the tale, you can introduce some activity or reflection. This only really works during a ‘beat’ in the story, that is when a natural breathing space occurs. An excellent example of this is the children’s story, The Very Hungry Caterpillar by Robert Carle. Carle makes the turn of every page an opportunity to ask the listening child a simple question such as “How do you think he feels now?” or “Why do you think he’s made that cocoon?” These are questions that don’t disrupt the flow but increase engagement by involving the learner in the storyline. Used appropriately, the reflection points build, not dilute, the dramatic tension and they do nothing to undermine the story’s climax.

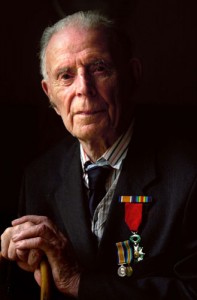

Finally we can use different, but related, stories as resources within our curated narrative. For example, on a piece on World War 1, you could image the historian and author Max Hasting describing, in the introductory ‘chapter’, how generals drove their armies into the ground followed by the visceral first-hand account of trench warfare from Harry Patch. In this case, each (self-contained) story builds on the previous activity to develop a sense of counterpoint and progression. If the consecutive stories do not increase the tension or challenge then they merely create a list, and lists are rarely engaging!

Finally we can use different, but related, stories as resources within our curated narrative. For example, on a piece on World War 1, you could image the historian and author Max Hasting describing, in the introductory ‘chapter’, how generals drove their armies into the ground followed by the visceral first-hand account of trench warfare from Harry Patch. In this case, each (self-contained) story builds on the previous activity to develop a sense of counterpoint and progression. If the consecutive stories do not increase the tension or challenge then they merely create a list, and lists are rarely engaging!

[I have talked about narrative and sequencing quite extensively in an earlier series of posts]

Integrating stories and using story techniques can tap into a fundamental form of human communication. Stories are perfect mechanisms for learning because they:

- hold our attention

- engage our emotions

- build complexity

It’s not rocket science – but it could be just as interesting.

Once upon a time there was an experience that changed a life – how do you think the story ends?