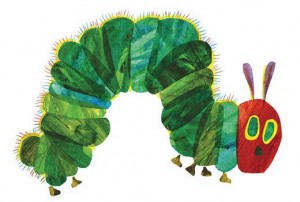

Aristotle & The Very Hungry Caterpillar

Storytelling is one of the oldest and most common forms of human communication. Well told stories engage us on the deepest emotional level, form indelible memories and make a profound impact on our lives. It’s hardly surprisingly that storytelling is such a popular phrase in today’s multiplatform world.

I have the immense pleasure of regularly leading workshops on storytelling and groups are always surprised by how timeless storytelling principles can be illustrated using the simplest of contemporary tales. A good example of this is Aristotle’s Poetics and The Very Hungry Caterpillar.

If like me you have fond memories from childhood, you may be more familiar with Eric Carle’s classic story (Amazon link) than Aristotle’s Poetics, the ancient Greek masterpiece which describes the Six Principles of Tragedy. Although Aristotle was describing the six elements of tragedy, I would argue that these principles are so insightful that they are equally applicable to any form of storytelling. What Aristotle described in 335BC (and Wikipedia lists as the earliest surviving work of dramatic theory) has remarkable resonance today and its features flourish in Carle’s story of the friendly grub.

If like me you have fond memories from childhood, you may be more familiar with Eric Carle’s classic story (Amazon link) than Aristotle’s Poetics, the ancient Greek masterpiece which describes the Six Principles of Tragedy. Although Aristotle was describing the six elements of tragedy, I would argue that these principles are so insightful that they are equally applicable to any form of storytelling. What Aristotle described in 335BC (and Wikipedia lists as the earliest surviving work of dramatic theory) has remarkable resonance today and its features flourish in Carle’s story of the friendly grub.

According to Aristotle “Tragedy … is an imitation of an action that is serious, complete, and of a certain magnitude; in language embellished with each kind of artistic ornament… Every Tragedy, therefore, must have six parts, which parts determine its quality – namely, Plot, Character, Diction, Thought, Spectacle, Song.”

Let’s use The Very Hungry Caterpillar to illustrate each one.

Plot

Our story follows an intrepid larva from birth through voracious appetite to transformation. Each page offers some new action. These dramatic events constitute the plot. As the structure of the incidents, the plot is the most important of all the elements, the “soul” of any story.

Character

The eponymous hero of our story shows his personality through his behaviour in each event. Aristotle’s character is the agent of action. It is character in the sense of personal disposition or nature as opposed the individuals themselves. It reveals their moral purpose and represents their temperament. Our caterpillar is a driven, almost reckless, soul, searching for fulfilment and willing to try anything that crosses his path. It’s a pursuit that puts him in mortal danger but ultimately redeems him.

Thought

Thought

The caterpillar’s relentless pursuit of food reveals the intellectual processes of the characters, their motivation, as well as the values and beliefs articulated in the story. The description of our caterpillar dumping the wholesome fruit and vegetables and gobbling up cakes and confectionary not only tells us something about the caterpillar’s priorities, it offers a cautionary tale about the consequences of greed.

Diction

Carle chooses his words very carefully; the use of language, the style and tone of the text creates a sense of wider context. As our caterpillar overindulges, so the language becomes more complex – the words reflect the action: we move from ‘apples’ and ‘pears’ to ‘chocolate cake’, ‘Swiss cheese’ and ‘lollipops’. Aristotle calls this expression of the meaning in words, diction.

Song

Although Aristotle originally talks about musical song, I think we can confidently translate this element into the rhyme and metre of the text. Each page of the story creates a melody for the drama. Each day beats out a rhythm for the caterpillar’s tale and the cacophony of consumption picks up the pace to breaking point. Finally exhausted (and sick) we slip back to the reassuring calm of “one nice green leaf” and the satisfied rest that precipitates the caterpillar’s ultimate transformation.

Spectacle

Spectacle

Spectacle includes all the aspects of the story that contribute to its sensory effects. For us, this is the physical presentation – the typeface, the illustrations and in this case, the drilled out holes in each of the foods through which we can poke a finger to mimic the caterpillars bite. Obviously not all stories rely on pictures, let alone physical holes in the media to fire our imagination but all the most engaging tales consciously draw vivid images in our minds and present themselves in such a way that they enhance the plot rather than distract from it.

Of Aristotle’s elements, two parts constitute the medium of imitation (Diction and Song), one the mode (Spectacle) and three the objects of imitation (Plot, Character and Thought). As we consider our own storytelling (in whatever form), it’s worth reviewing these ancient insights and maybe, just maybe, our stories will emerge like beautiful butterflies too.