What Games are Good For?

In spite of my criticisms of many educational games, I believe passionately in the potential of games to inspire learning. I don’t think that games are a panacea but they do have many characteristics that can make a profoundly positive impact on our lives. The real educational value for gaming lies in four key areas:

- Cosmetics – making the unpleasant or mundane more palatable

- Confidence – offering the chance to practise and fail softly

- Catalyst – as a spring board to further investigation

- Collaboration – as a means of pooling our intellectual and social capital

Cosmetics

For many years we have adopted game mechanics to make ordinary activities more engaging. Recently that process has gained a higher profile and more glamour through the term “gamification.”

The most common form of educational game is the quiz. A quiz is simply, a glorified, gamified, test. I’m not being disparaging, on the contrary: there is no doubt that ‘treating’ assessment in this way makes it more engaging without diminishing any of its quantification value. Quizzes make the process of testing knowledge more enjoyable but you still need to identify the right answer to progress.

Although mainly used to check knowledge, this same approach can help raise awareness and change behaviour. It’s a technique deployed for loyalty reward points such as Air Miles, travelling (Foursquare and Gowalla) and environmentally-friendly driving behaviour (Toyota Prius, Nissan Leaf, etc.)

Confidence

There are many circumstances where we want to practice before being exposed to a real situation. Those circumstances might be technical, financial or social but where getting it wrong in reality might cause real problems. Games provide the perfect environment to practice, to experiment, to fail softly.

It goes without saying that we’d prefer our airline pilots to train using simulators before taking the controls of a real jumbo jet. Games can also provide a proving ground for social interactions, leadership skills, teamwork. Although the fidelity of the game is unlikely to present an entirely true mapping with reality, the experience of playing within a recognisable environment helps develop important, transferable, understanding. I suspect the translation to reality will always need some additional contextualisation and the scaffolding but it does at least prepare the ground, and even if the game and reality are radically different it can help the player feel more confident.

Catalyst

Where games have proved to be enormously valuable is when the experience has been scaffolded or supported by an enthusiastic teacher who can use the game play as a stimulus for other activity. Good teachers (formal or informal) can draw out of the game transferable lessons such as urban planning from SimCity, rotational geometry from Tetris, creative writing from Myst or social etiquette from the Sims.

In these circumstances, the accuracy of the game is less important than its ability to engage:

Jonny Ball famously said “Don’t let the facts get in the way of a good joke.”

Games are excellent in their ability to bring a subject to life, encourage exploration and provoke further thought. Even if a game is not strictly true in its representation of objects or events those inaccuracies can form a powerful stimulus for further investigation and discussion. From my own experience, I know that the flaws in games can prove powerful provocations for debate and that that can generate profound learning.

Collaboration

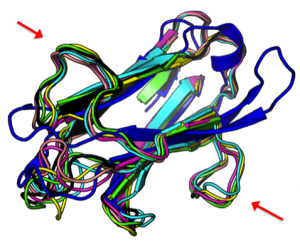

The combined problem-solving activity of the gaming world is racking up some astonishing figures – people have played World of Warcraft for an incredible 6 million years of combined effort since its launch in 2004. The biggest growth area in gaming is multiplayer games with millions of players around the globe regularly engaged. And the activity is predominantly team-based – these are virtual communities at ‘work’. That shared experience, that voluntary collaboration – “cognitive surplus”, as Clay Shirky might call it, “blissful productivity” Jane McGonigal might say, can be channelled into very valuable focus such as the example of gamers identifying the structure of a new retroviral enzyme.

There is something deeply satisfying about solving a problem, beating a challenge or experiencing something new when it is done with others. The social nature of online gaming has great potential to bring people together for a common purpose.

Imagine if we made more use of that combined effort: what other real world problems and challenges might gamers solve?

I have no doubt whatsoever that games can make a unique contribution to education and society. I think that in the past we have, perhaps, been overconfident in our expectations: wrongly assuming that games on their own could solve many, if not all, of the barriers to learning. However, if we take the true characteristics of games and embed them in a well thought through set of experiences then we have something that will be genuinely different and make a genuine difference.